Confouding Variables

Here, I spoke about independent & dependent variables.

The below explanation uses these terminologies.

Contents

Intuitively,

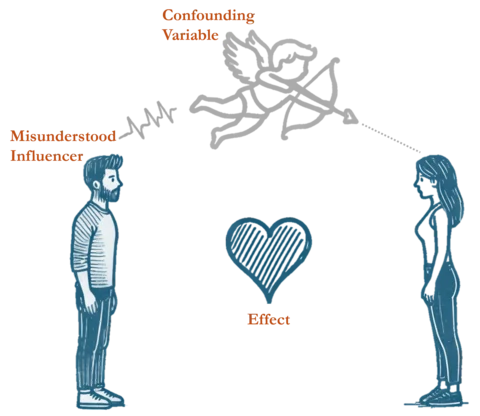

When we are studying the relationship between two variables (independent <-> dependent, or 2 independents) there may be a third (hidden) variable secretly influencing both your variables. This hidden variable is called the confounding variable.

Popular examples are usually those of spurious correlation, where two seemingly unrelated variables with high correlation are claimed to have a cause-effect relationship. Let’s take the case of, increased ice cream sales leading to more people dying. At first glance, this seems ridiculous. There is no direct reasoning for death toll to increase simply because ice cream sales are going up.

It seems like we have a hidden actor, a confounding variable. A variable secretly exerting effect (like a spy) on both the variables - such that when we only observe the effect, without this hidden actor, we are left confounded. In this case, the confounding variable is temperature - as temperatures increase, people buy more ice cream. And as temperatures increase, so does the incidence of heat strokes leading to increased deaths. An increase in temperature increases ice cream sales & deaths by heat stroke, independently. However, without temperature data, some people may wrongly conclude that increased it is ice cream sales that caused the deaths!

Let’s look at another example where the confounding effect is less obvious, and hence, we’re less likely to detect its presence. Let’s take the case of coffee consumption and work performance. Your study shows that increased coffee consumption leads to a better work performance - is this causation or spurious correlation? The result may seem agreeable to you, especially if you’ve been a coffee drinker or are surrounded by a coffee culture.

🌌 Tangent: Why? due to our confirmation bias - we are more likely to easily believe evidence that reaffirms are beliefs. That is, we’re less likely to question the accuracy of such results, which is contrary to one of the tenets of being a data professional - be equally skeptical about everything.

In your research, the hidden variable (the confounding variable) may be sleep quality. Perhaps, poor sleep quality drives your research participants to drink more coffee to be able to work better. Here, coffee consumption is simply a variable caught in between the effect of sleep quality on work performance.

In summary, a confounding variable is a hidden variable (not part of your data) that influences one or more of your variables, and has a strong correlation with the misunderstood influencer. In the above examples,

- temperature (confounding variable) had a strong positive correlation with ice cream sales (misunderstood influencer) and was the real cause behind deaths (effect).

- sleep quality (confounding variable) had a strong positive correlation with coffee consumption (misunderstood influencer) and was the real cause behind changes in work performance (effect).

In short, confounding variables, or confounders, distort the relationship between variables.

Mathematically,

There are no mathematical formulae for auto-detecting confounders or their effect. What exists are tried & tested ways to avoid/reduce confounding effects from distorting your results.

Note: This requires you to critically examine your dataset and analysis methods.

Statistically,

Here are a few ways to do away with confounders:

-

Randomize your dataset: Ensure that your sample is truly randomized & representative of the population (be vary of selection biases). This will minimize the confounding effect by letting chance play a greater role in sampling.

For the first example (above), include ice cream sales & death statistics randomly from different regions to minimize the effect of temperature in skewing the results. Here, you may easily learn that, when an equal proportion of hot-cold-temperate climates are sampled from, there is no correlation between ice cream sales & death tolls. -

Apply segmentation or stratification: This requires you to pre-empt possible confounding effects based on your domain knowledge (expert knowledge about the research subject). In our second example (above), you may know upfront that variables like hours of sleep, work hours, employee experience, etc. may also effect work performance. Instead of including these in your effect modeling, you may choose to cluster or segregate your data on the basis of these possible confounders and measure the relationship between coffee consumption & work performance independently within all clusters. The results may clearly show that cause-effect relationship isn’t as universal (across all clusters) as we had initially thought.

-

Take statistical control: This is a more direct approach in adding the expected confounders directly to the model and performing multiple regressions fine tune the truer effect of coffee consumption on work performance. If the other confounders indeed have a greater effect on work performance, the relative contributing power (beta co-efficient) of coffee consumption will reduce in the model.

-

Introduce instrumental variables (IVs): This is a special class of variables that are correlated with the independent variable (misunderstood influencer) but not with the dependent variable (affected variable). At the risk of multicollinearity (increasing the influence/weight of a set of correlated variables since it is similar to double-counting a variable), this helps to isolate the truer effect in scenarios where it is difficult to gather data on the confounders (due to data collection/quality issues/etc.).

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: